Notes From the Met, the Whitney and the New York Public Library

The fifth and final chapter from five days in New York.

As pretentious as it may sound, I always find the most enriching part of any trip to be the hours spent wandering round museums and galleries. Ideally alone. That was definitely the case with New York, where, by the final day, I was feeling under the weather and sleep-deprived and a Sunday afternoon at the Met and the New York Public Library re-energised me. Earlier in the week, I’d visited the Amy Sherald exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and, despite my gripes, I still can’t imagine a more uplifting way to have entered my thirties. Finally, I stopped by the Malick Sidibé show at Jack Shainman in Chelsea, where my main takeaway was that New York gallerists don’t seem to despise everyone who walks in like they do in London.

Below, my mini review of each show.

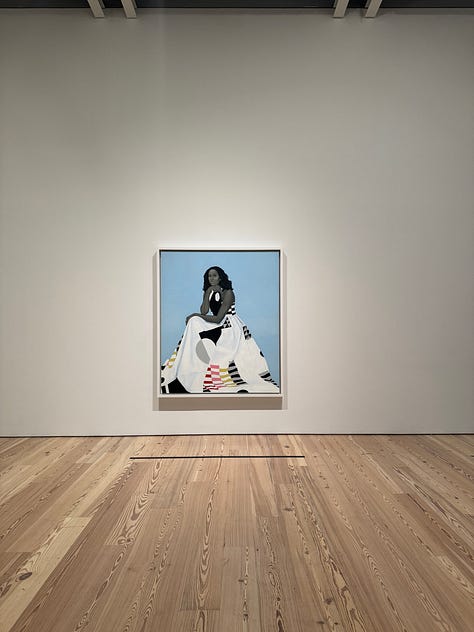

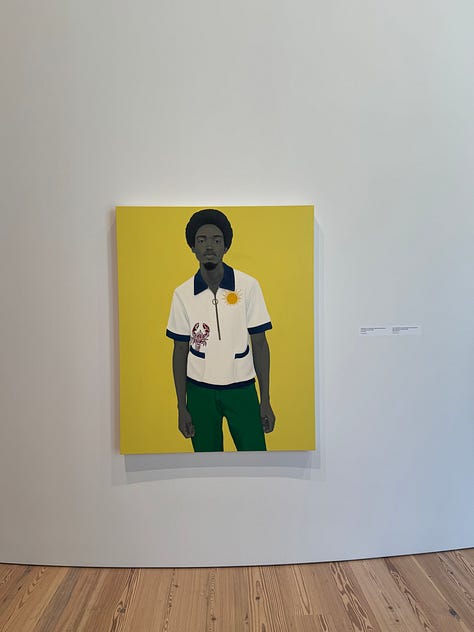

Amy Sherald: American Sublime at the Whitney Museum

As a lover of Black portraiture, I booked in to see this major retrospective of Amy Sherald’s work before we left for New York. This exhibition included her career-defining painting of Michelle Obama which I admittedly had felt was a poor likeness when it was revealed back in 2018, but which I’ve since decided completely captures her persona as First Lady: self-possessed yet resolutely private. Her painting of Breonna Taylor is more poignant in person than it could ever be through a screen, and for the first time I noticed echoes of one of my favourite artists, Barkley L Hendricks, in Sherald’s work, such as the gorgeous ‘A bucket full of treasures’.

Now, I’ll be totally honest: I find some of Sherald’s pieces a little heavy-handed in their symbolism; a reinterpretation of the VJ-Day image with Black queer men is just a tad obvious to me, in the same way as artists whose entire oeuvre consists of depicting Black people in the manner of Old Masters. (Okay, and…?) But, at the same time, I’ve never subscribed to the idea that Black art has to be raw or personal or challenging in some way for it to cut through, and I genuinely found a lot of relief that day in her graceful, somewhat mundane depictions of Blackness, even more so when complemented by the Whitney’s panoramic views of the city.

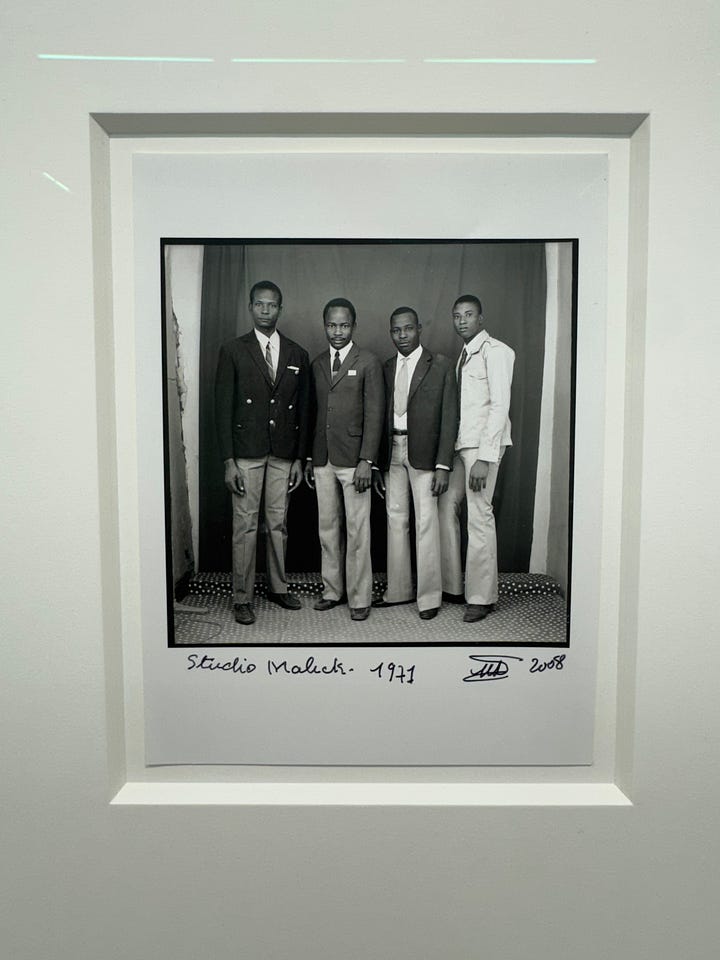

Malick Sidibé: Régardez-moi at Jack Shainman

Staying at Hotel Chelsea meant that New York’s gallery district was just a short walk away, and so there was no chance of skipping the Malick Sidibé show at Jack Shainman. Sidibé was a celebrated Malian photographer who died in 2016 and has since won a new generation of fans after his 1963 ‘Nuit de Noel’ portrait started circulating on social media. As someone from the West African diaspora, viewing his work can feel especially resonant, like flipping through a forgotten family album. I spent several minutes poring over his wedding photographs and couldn’t help but be struck by how modern everyone looked, and how it all felt so familiar. Perhaps with Black dandyism on the brain, I found myself especially drawn to his male subjects, standing proud in their sharp suits and hats and sunglasses. I’ve since added half of these pieces to my Artsy favourites for when I have a few thousand to spare.

Critics of Sargent view him as a painter-for-hire for the 19th-century élite. I can’t help but swoon over his portraiture: not just that he depicted beautiful, glamorous people in expensive clothes (an enduring interest of mine) but specifically the luxuriousness of his brushstrokes and the way he lit his subjects and brought their essence to life. Having seen these works in person, I can understand even more why everyone was so desperate to sit for him.

The exhibition title is a little misleading: it’s really about Sargent’s early years, which were spent mostly in Paris but not exclusively, and though I came for the opulence, his non-commissioned paintings of ordinary people on the streets of Italy and Spain suggest he was more of an anthropologist than some might give him credit for. There’s an entire room dedicated to his best-known work, ‘Madame X’, which created so much scandal that he eventually had to flee to England. However, in my view, it’s not nearly as sensual in real life as his depiction of Dr Pozzi, a physician-about-town dressed in red robes who still oozes charisma 144 years later, or as compelling as the slightly creepy ‘Daughters of Edward Darley Boit’.

I’d also hoped to get an early peek at Superfine: Tailoring Black Style as I’d planned to write about it for a menswear magazine, but despite my pleas and many, many emails, this was strictly out of bounds before the press preview on 5 May.

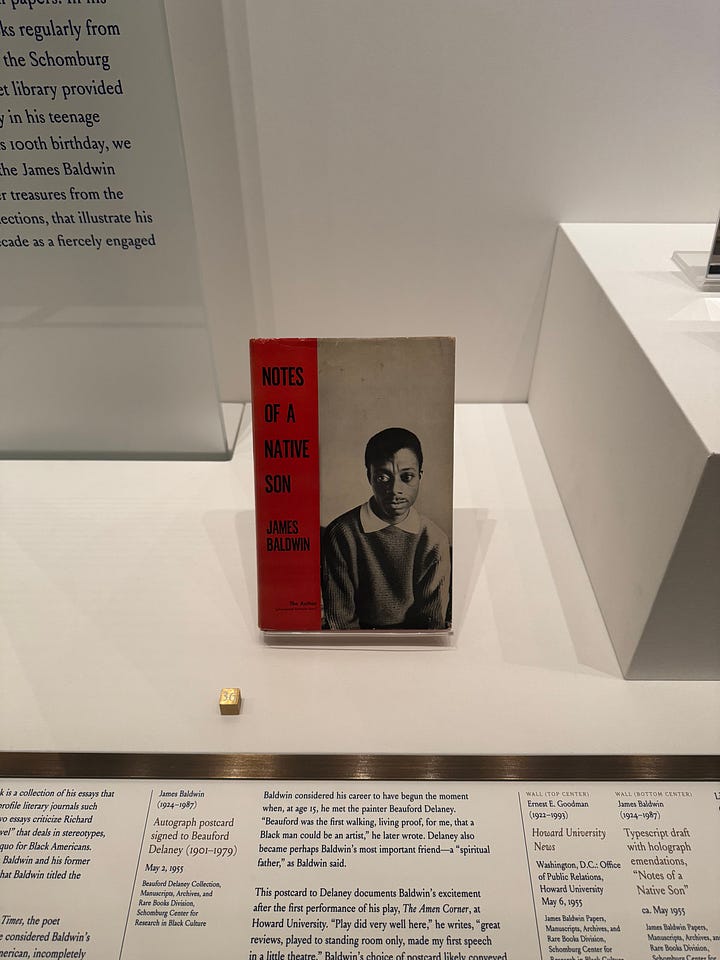

James Baldwin and New Yorker centenary displays at the NYPL

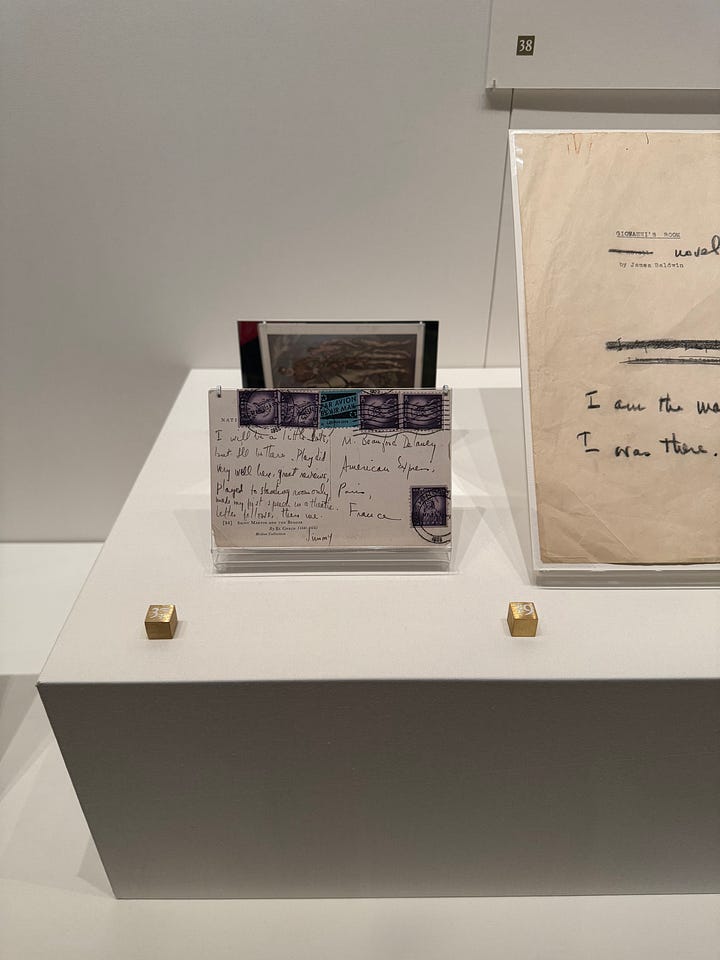

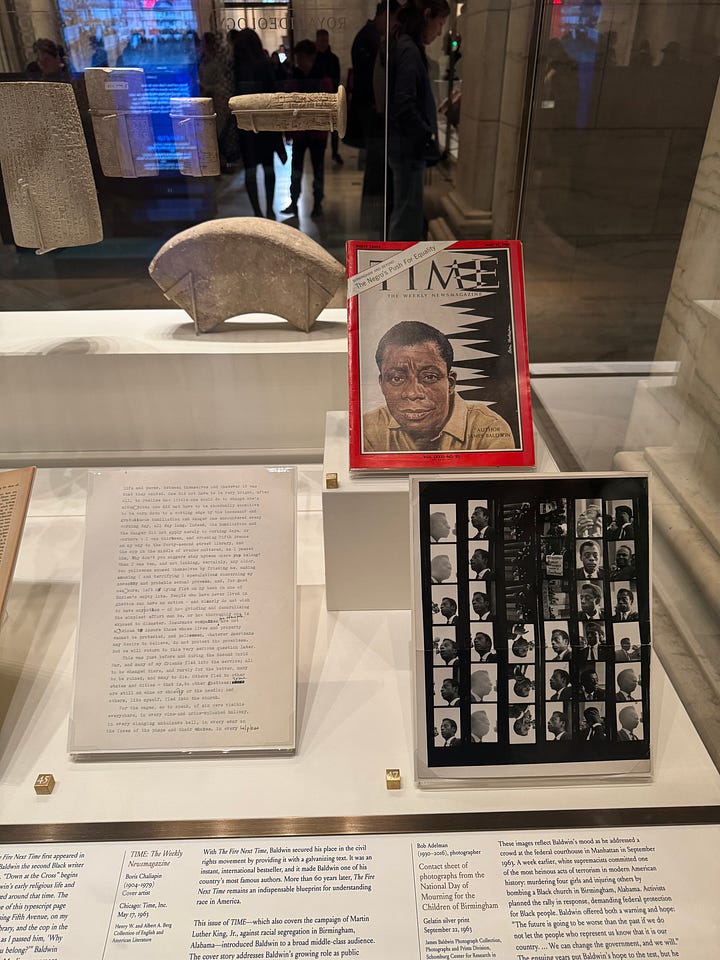

I didn’t expect the New York Public Library to be absolutely rammed with tourists, which inevitably made it less enjoyable (yes, I know I was technically one of them), but I’m still glad I dropped by. I was there for the centenary display for James Baldwin, although this turned out to be just a cabinet. Even so, I was reminded of Fran Lebowitz’s words about how seeing a writer’s handwritten notes immediately draws you closer to them. And as someone whose fascination with Baldwin goes far beyond his work (you know how some girls are obsessed with Joan Didion), viewing a postcard to his dear friend and mentor Beauford Delaney and an annotated manuscript of Giovanni’s Room felt as intimate and rare as glimpses go.

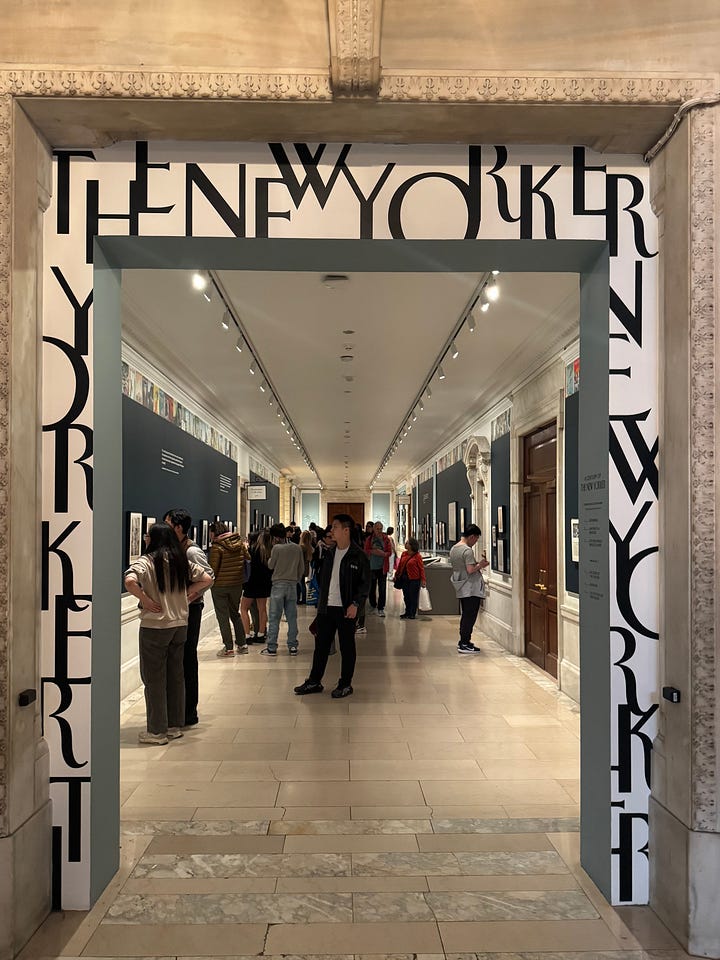

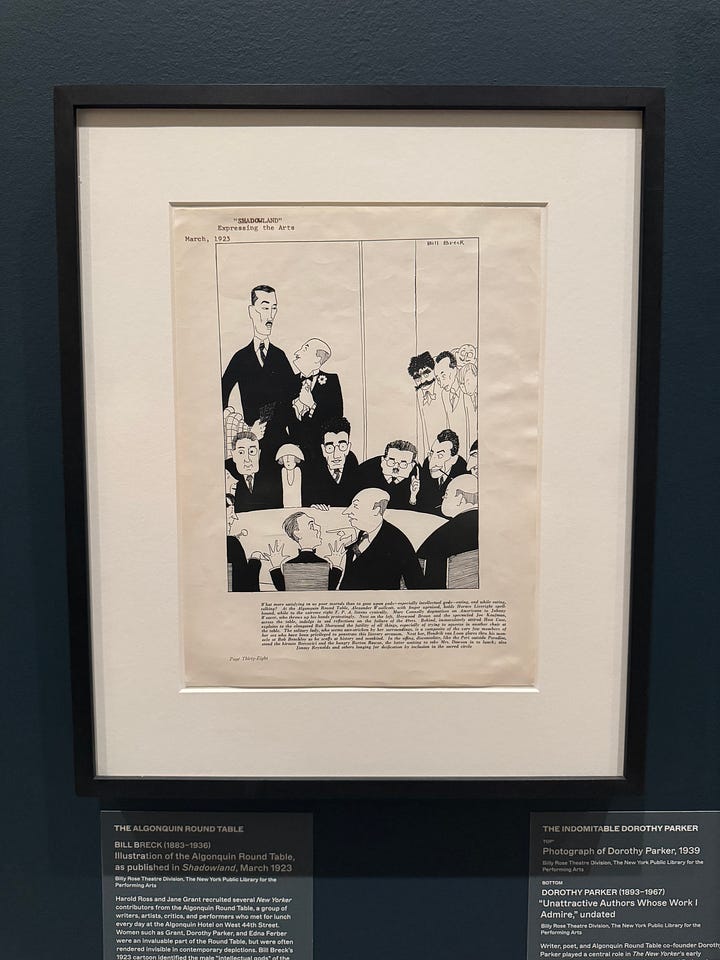

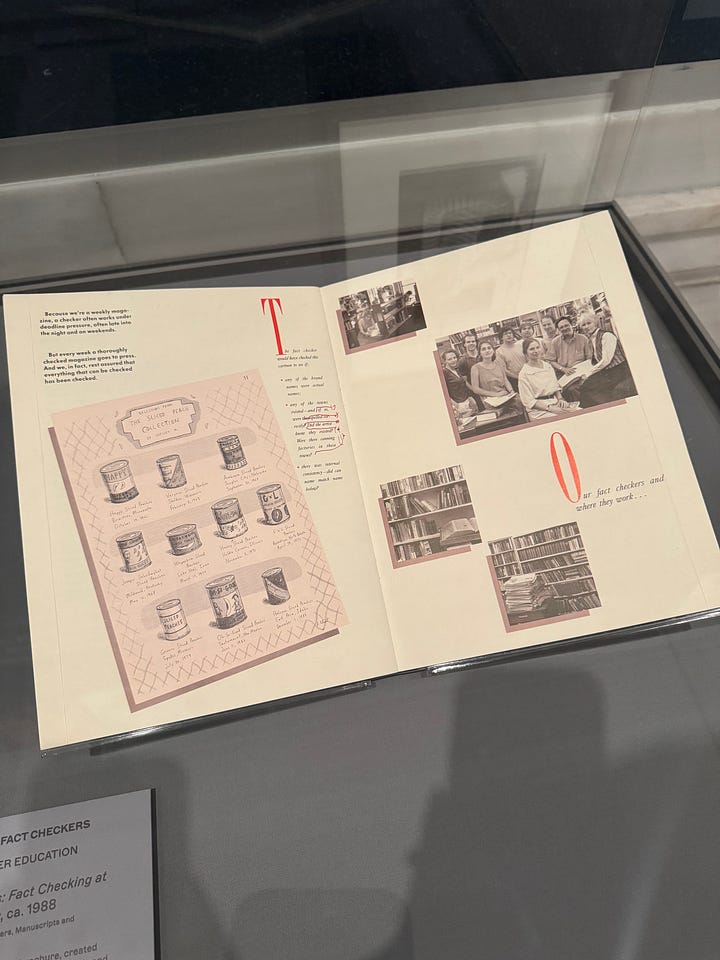

As it happens, another American icon was born not long after Baldwin, and upstairs was a delightful exploration of the New Yorker’s history. Like most writers, I’m prone to romanticising the world of print pre-internet, and browsing through the archives at this exhibit felt a little like stepping into The French Dispatch. Honestly, I whizzed through it all because it was time to head to the airport, but not before I made a mental note to check out the writings of long-time Paris correspondent Janet Flanner and to pick up the world’s best magazine more often.

Further Reading

Amy Sherald, Brazen Optimist in The New York Times

Amy Sherald’s Blue Sky Vision for America in The New York Times